What Will Russia’s Dissolution Look Like and Should One Expect That?

The fall of empires is usually difficult to predict, as empires are convincing in transmitting the idea of their invincibility, both domestically and internationally. Nevertheless, they regularly collapse, and this process often happens overnight. Russia is facing the same destiny.

Any discussion about the likelihood of Russia’s dissolution starts with the question if such a collapse could happen in the absence of a persistent national liberation movement in today’s Russia. Many believe that chances for Russia’s dissolution are low as long as there are no officially registered political parties calling to establish an independent country of Tatarstan or regular anti-government protests in Bashkortostan’s Ufa, or Udmurtia’s Izhevsk.

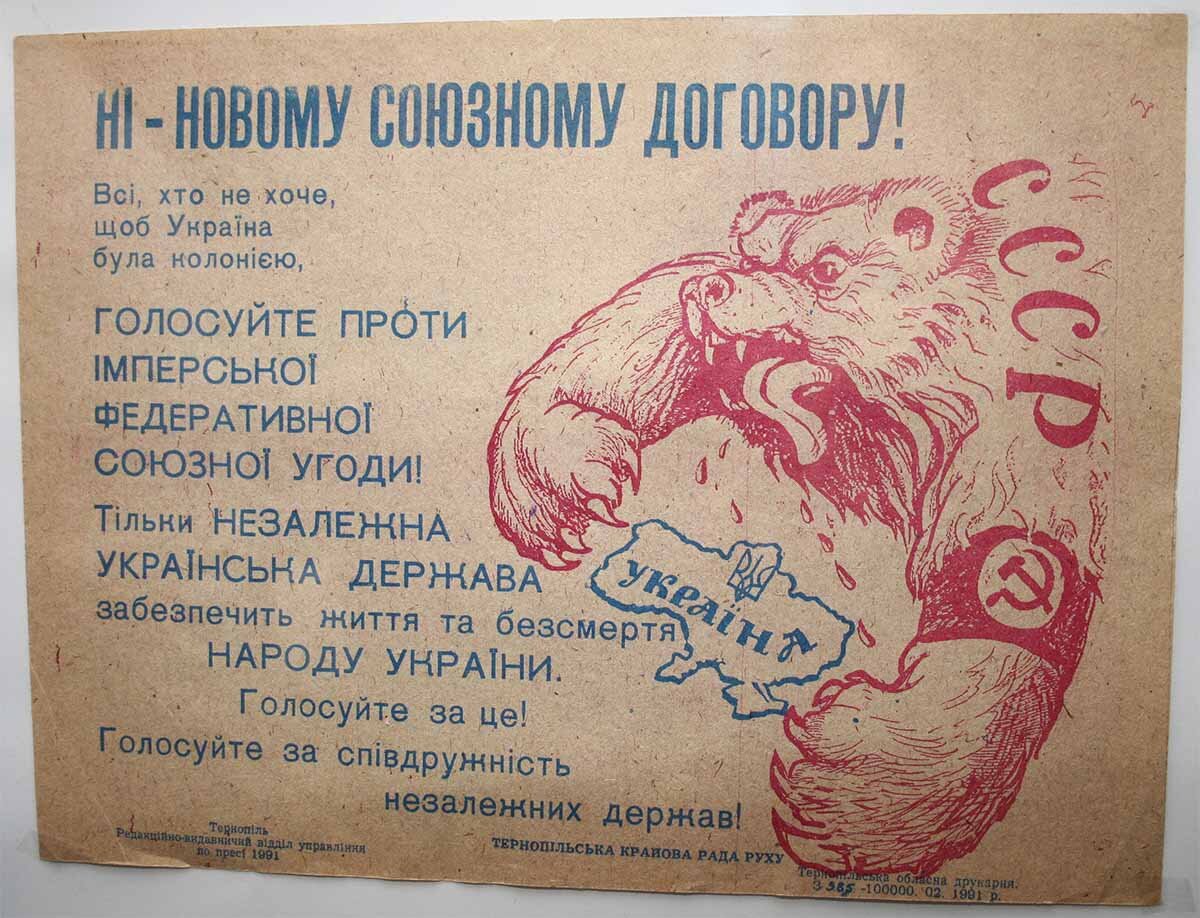

However, such an assessment contains a grave error. One should not expect a country that restricts any legal possibility for protests, to have public movements openly demonstrating their secessionist intentions. Moreover, a change of sentiment from perceived apathy to active support for an independence idea could happen instantaneously. One could recall that over 70% of Ukrainians, who took part in the Ukrainian sovereignty referendum on the 17th of March, 1991, voted in support of Ukraine remaining part of the Soviet Union. Their share in the whole population amounted to 58%. However, already in December of the same year, 90.3% of the voters, or 75.98% of the population, approved the declaration of independence. What happened to public attitudes within these nine months?

A poster dated on 1991, urging to vote for the independency of Ukraine

First, the Soviet Union’s imperial government demonstrated its weakness in August 1991, when the radical Communist Party started, but failed to execute a coup d'état. Second, Ukraine’s Supreme Soviet adopted the Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine, effectively setting up a format of, and vector for, a new independence movement. The country’s population, which had not believed in Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union just nine months ago, found itself in a new political reality and instantly accepted it.

There are no obvious reasons to expect that Russia’s dissolution would follow different rules. This process will be a continuation, thawing of the USSR dissolution and will follow its pattern. The dissolution of Russia will complete those processes that started in the USSR in the 1980s, similarly to World War II, that had been a continuation of World War I after the 1918-1939 armistice and had put an end to Germany’s attempts to become the military hegemony of Europe.

One should not forget that Soviet republics were not the only ones who adopted declarations of independence in 1990-1991. Starting from July 1991, 15 regions of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) also declared their independence, including the regions of Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, Chuvashia, Komi, Mari El, Kalmykia, Sakha, Buryatia, Tuva, and Udmurtia. Regional constitutions of most of these regions start with declaring that the nature of their relations with Russia is a mere association enshrined in the treaties on delimitation and mutual delegation of powers between the region and the Russian Federation. These legal norms are dormant at the moment. However, they could be resuscitated at any time, similarly to the self-determination right reactivated by the Soviet republics when Moscow demonstrated its inability to keep its empire under control. In modern Russia, the Moscow centralist authorities have been persisting in curtailing the powers of regional authorities, for instance, by stripping governors off their regional presidential status. Such actions are likely to intensify the processes of regional separation by providing additional reasons to maintain the list of grievances Moscow has inflicted on their peoples.

Who Will Go Nuclear First?

One should not abstain from making bold assumptions when analysing the possibilities of Russia’s dissolution. Otherwise, one will make the mistake of George H.W. Bush of being over-confident about the stability of the USSR political regime as late as in August 1991, when he travelled to Kyiv seeking to convince Ukrainian MPs to keep Ukraine as part of the Moscow empire. Currently, Russian regions are torn with internal conflicts, which could play the similar role in Russia’s disintegration as domestic conflicts of the 1980s played in the dissolution of the USSR.

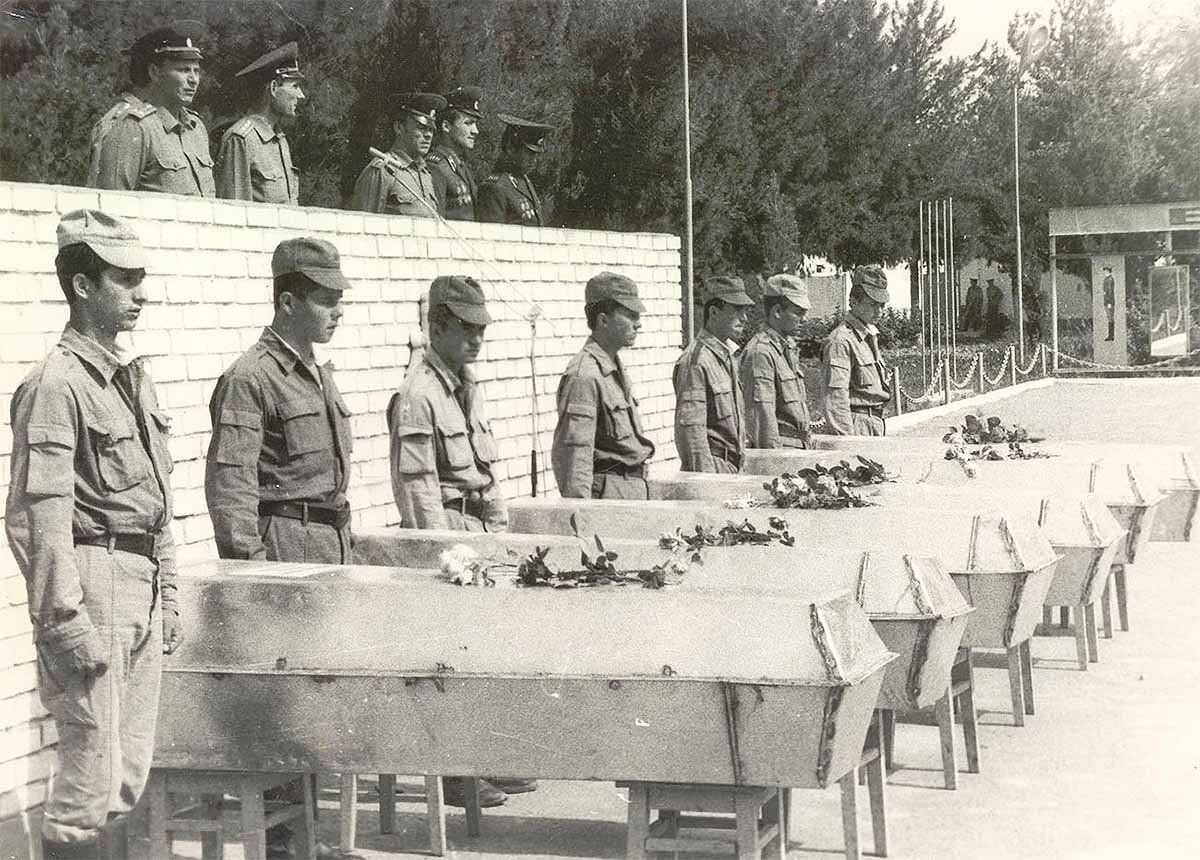

A term cargo 200 (KIA) came into use during the Soviet-Afghan war

What might Russia’s dissolution look like? History demonstrates that the fall of any empire usually begins when a metropolis demonstrates its weakness. The USSR demonstrated such a weakness in its military defeat in Afghanistan and, arguably more articulated, in its inability to establish a functioning economic system and a political reality that would allow the Communist party leaders to transform their political power and semi-legal property ownership rights into a legal inheritance for their children. The USSR began to collapse when republican elites realised the disadvantage of continuing to hold on to Moscow. The first secretaries and Politburo members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, for instance Aliyev in Azerbaijan, Shevardnadze in Georgia, Kravchuk in Ukraine, and Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan, became overnight the leaders of independent countries. This was their way of avoiding the toxic vassalage relations with Moscow. Their former boss, the USSR’s General Secretary Gorbachov, turned into a political retiree already in 1992 and had to sustain his livelihood with royalty payments from Western universities, while these former Soviet republican elites were ruling UN member states. Some of them, for instance, Nazarbayev, managed to gain almost life-long power; others, such as Aliyev, established quasi-monarchies with an unspoken right to transfer their power to their children.

Russia’s dissolution is likely to follow the same path. If the current leaders of Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Udmurtia and Sakha manage to get free from Moscow’s control, they would be able to obtain the indulgence for their role in building President Putin’s political regime and to ensure the financial stability of their regions through a direct participation in international trade. The only current Russian governor, whose fate could be threatened by Russia’s disintegration, is Chechnya’s governor Ramzan Kadyrov. He is likely to be revenged violently by those Chechnya residents, whose relatives he has killed. All other regional leaders are likely to gain from Russia’s collapse.

As of now, the Yamalo-Nenets autonomous region has the largest Russian oil fields

The biggest share of Russian natural resources, which are largely sustaining Moscow’s public budget, are located in Russia’s ethnic minority regions. The Yamalo-Nenets autonomous region has the largest reserves of natural gas amounting to 40trln cm, followed by Astrakhan region with 4trln cm. The top-three oil depositing regions are Khanty-Mansi autonomous region, Yamalo-Nenets autonomous region, and Tatarstan. The existing Russian economy system is based on the redistribution of profits for these natural resources from regions to the country’s capital of Moscow. In 2010-2019, urban planning projects in Moscow cost 1.5trln of roubles, or 20.4bn euro, while all the other Russian regions spent 1.7trln of roubles, or 23.2bn euro, for similar projects. In 2019, the public budget of the city of Moscow amounted to 2.8trln of roubles, or 38.2bn euro, followed by the city of St. Petersburg with 665bn of roubles, or 9bn of euro, and eight cities, whose budgets varied from 10bn of roubles to 44bn of roubles, or 136mn of euro to 600mn of euro. A chance to gain control over these profits, instead of transferring them to Moscow, could play a significant role in encouraging local elites to secede from Russia.

The Presidential Palace in the city of Grozny, Chechnya region, in January 1995

However, any attempt to secede from Russia comes with great risks. Moscow has already demonstrated what it is capable of doing to preserve its control over the country’s territories in Chechnya region in 1994-2000. That is why Russia’s dissolution process can only start after Russian regions recognise Russia’s military and police impotence.

A first sign of Russia’s collapse is likely to take the form of civil unrest in the North Caucasus or other poor and socially vulnerable regions, likely with a large share of the Muslim population and long-perceived oppression in Russia. Such riots can be triggered by seemingly unrelated events. In December 1986, large-scale uprising erupted in the city of Alma-Ata (today Almaty), Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, after students took to the streets in protest of the appointment of ethnic Russian Kolbin to the post of first secretary of the Kazakh Communist Party. In May 1989, riots broke out between the Meskhetian Turks exiled in Uzbekistan and the native Uzbeks. There were plenty of similar conflict situations in modern Russia. In Bashkortostan in 2020, protesters clashed with the National Guard’s special police unit forces, while defending sacred hills, shikhans, from their destruction for limestone mining. Similarly, in Arkhangelsk region, residents joined protests seeking to stop garbage trucks from disposing of their content, collected in wealthy Moscow, in local landfills.

The protests in Alma-Ata (today Almaty), Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, in December 1986

It is impossible to predict what would be the last straw to break the camel’s back. It could be protests triggered by the forced mobilisation of the youth in the North Caucasus, language discrimination and self-immolation of academics in Udmurtia region, or sexual assaults of women and girls by ethnic Russians. Such protests are perfect to start a country's dissolution due to their sudden and rapid development, largely impossible to foresee or to halt. However, knowing the exact cause that will ignite such a process is not that essential. More important is the number of the dissatisfied youth, the existence of horizontal social contact networks, and the possibility to rapidly mobilise, for instance, on ethnic or religious grounds. If the Moscow police fails to take such an evolving protest situation under their control, other regional leaders would be convinced of Moscow’s failure to respond in time.

Such development could trigger a parade of regional secession. The key role in this parade will not be played by the spontaneously consolidated youth, but cynical regional leaders, who demonstrated their loyalty to President Putin just a few days ago. Similar to Ukraine’s communist party member Kravchuk using the vision of idealist dissident activist Chornovil for the transit of power, Putin’s regional elites in Tatarstan and Bashkortostan would hijack the political slogans of naïve activists, who dream of independence but lack control over the state apparatus and financial resources.

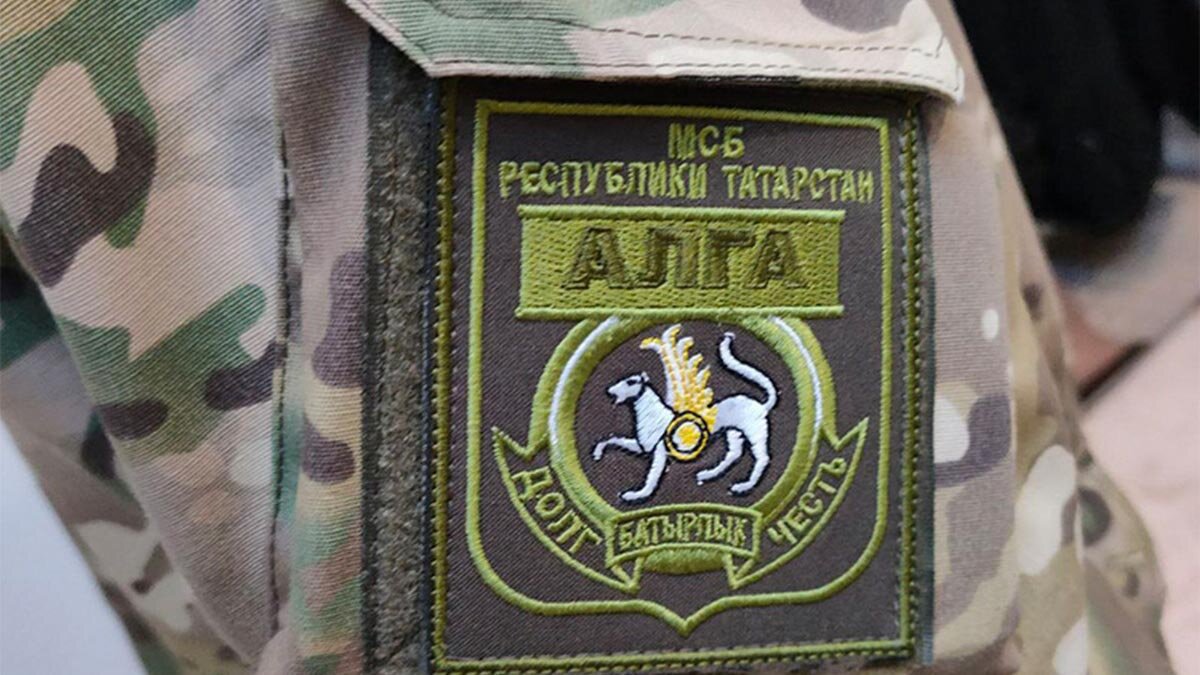

In early February 2022, Tatarstan’s volunteer battalion Alga was sent to conduct military operations on Ukrainian military positions in Donbas. The exact number of casualties is still unknown

Russia’s federal political elites seem to start feeling such a threat. Russia’s state-owned corporation Gazprom has established a private military company, likely to maintain control over its gas fields and key infrastructure facilities. In parallel, regional elites have been creating national volunteer military battalions under the pretext of supporting Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In reality, such volunteer army units, for instance, Tatarstan’s volunteer battalion Alga could represent a first attempt to form a focal point for future regional armies. Similar to Ukraine’s Sich Riflemen nationalist unit formed within the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, regional nationalist army battalions in modern Russia could swiftly turn into a fighting force of the newly forming states.

From Russian Regions to Post-Russian Countries

Is there a prompt legal mechanism to recognise the independence of these new countries? It is paradoxical but the collective West could become the biggest opponent of such a process. Their concerns that Russia’s dissolution would turn to chaos could inhibit the recognition of the independent status of these new countries. At the same time, the likelihood of their international recognition will depend primarily on how stable these countries would maintain control over their territories. If they manage to demonstrate it, the West will have to recognise a new status-quo.

The most conservative theory of state law, the German doctrine, states that a sovereign country comprises three mandatory elements: all the national population (Staatsvolk), its territory (Staatsgebiet), and state power (Staatsgewalt). Thus, a country to emerge and to gain recognition by others needs the people, who identify themselves with this country and could discern those who belong to their community and who do not. This country needs a relatively well-defined territory and a means of exercising control over this territory.

There are already several republics in Russia that meet these criteria, such as Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, possibly Kalmykia, and Sakha. These regions’ populations are able to self-identify their unique language, and even religion which distinguish them from the Moscow-oriented Russians. A leading ethnic minority constitutes the largest share of the population in all these regions, but Sakha. In Sakha region, the domestic ethnic minority comprises 49.9%, but ethnic Russians are still in the minority. In addition to ethnic Yakuts, the region is populated by the Evenks, Ukrainians and Tatars, totalling 10% of the population. Tatarstan and Bashkortostan regions have a population of over four million, similar to Slovakia or twice as large as Latvia.

A protest in Tatarstan in 1990

These regions have clearly defined borders enshrined in their constitutions. They also have state-level agencies: a president (recently renamed in some constitutions as head of the region), a parliament, and a supreme court. Some of them have the century-long histories of nation state-building or national resistance movements. In the 18th century, the Bashkirs rebelled so often that they were eventually prohibited from working as blacksmiths in an attempt to prevent the production of weapons. Ethnic Bashkir Salavat Yulaev was the right-hand man of Yaik Cossacks uprising leader Yemelyan Pugachev and led the Bashkir cavalry. In the Soviet mythology, Yulaev was declared a fighter against the tsarist regime. As a result, almost every Bashkir village has a street named after him, cities have monuments praising him, the main hockey team of Bashkortostan and several enterprises bear his name. This story of regional resistance suits well to build a national idea of independence. The Bashkirs already have their symbolics, including a flag, a coat of arms, an anthem, and even a national musical instrument, the kurai, to support national state-building with a national idea.

A monument to Salavat Yulaev in the city of Ufa, Bashkortostan region

The Tatars could also build a new national identity based on their unique historical experiences, the abundance of poets and writers in the early 20th century, and the history of national resistance to the Moscow invasion. For example, Tatar nationalists still mark the anniversary of Ivan the Terrible’s capture of Kazan in October 1552 as a day of mourning, which could unite this nation around the memories of their lost statehood.

Many other Russian regions will be less fortunate. It is difficult to imagine that such heavily Russified or economically poor regions like Udmurtia, Chuvashia, Buryatia, and Altai will be able to instantaneously build their independent statehood ideas. Their fate will likely depend on how promptly Tatarstan, Bashkortostan and other central Russian regions declare their independence. If it happens swiftly, Russia will be geographically separated into two parts and will lose its logistical connectivity. In contrast to the USSR dissolution in the 1990s, these new post-Russian countries will be established not in the periphery, but in the centre of the current empire.

In such a scenario, even not the strongest political regions could join the separatist movements. The formation of independent federations could be expected among the Volga and Kama people, who could unite enslaved nations with populations smaller than in Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. Siberia could also create a flexible supra-state nation, likely under China’s economic control and political protectorate. Other countries, which could join the competition for political influence in the post-Russian space, are Turkey, Azerbaijan, probably Kazakhstan (Turkic minorities), China (Siberia), and Ukraine (the North Caucasus, Kuban, Volga, and central Russia). Once it commences, this liberation movement will cover a large part of Russian regions, leaving only those territories that associate themselves with the current Russian narratives and cannot escape the imperial logic, as part of Russia (Muscovy).

A Buryat shaman on the shore of the Lake Baikal, contemporary Russia. Arkady Zarubin, CC BY-SA 3.0

What Should Ukraine Do?

One of the most important contributors ito the process of the Russia’s dissolution, Ukraine, should look at this process exclusively through the lens of scenarios that will ensure its strategic security. Strategic security implies living in peaceful conditions for at least 20-30 years. Ukraine’s 30-year independence prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion ensured that Ukraine had enough people who were willing to fully associate themselves with Ukraine and to fight for its existence. A conventional invasion of a similar scale in 2010 would have had a divergent outcome. In the next 30 years Ukraine needs to ensure a political and social environment free of permanent counteractions against Russia’s threat. Funds saved would help the country achieve a sustainable leap in economic development and political influence in Europe. Therefore, post-war Ukraine should focus solely on developing scenarios of its sustainable security.

In a nutshell, there are three such potential scenarios. All three scenarios are based on the assumption of Ukraine’s victory against Russia in the latter’s continuing invasion. Otherwise, there is no point talking about Ukraine’s security. However, these scenarios differ in their projected consequences of a Ukrainian victory for Russia.

A first scenario envisions Russia maintaining its current political regime, with current President Putin or his close ally remaining in power. This is a negative scenario for Ukraine, as it implies that Russia will continue its subversive activities against Ukraine. The threat of a future invasion will remain high. The only positive matter for Ukraine in this scenario is that Ukraine’s population and the EU will share an understanding of a continuation of the confrontation with Moscow. Hence, most international sanctions against Russia will likely remain in place.

Hostomel, Kyiv region, after the Russian occupation. Oleksii Samsonov, CC-BY-4.0

A second scenario entails that a new political regime emerges in a military defeated Russia. This regime is headed by Russia’s seemingly liberal opposition or, more likely, Putin-linked public officials, who will be seeking to make an impression of the true liberal opposition. Their leader could be a local public official, who became a vocal opponent of President Putin just in time for the power transition. Such a scenario already happened during the Gorbachev downfall, when future President Yeltsin emerged as an anti-establishment leader. This is the worst political scenario for Ukraine. The collective West will use such a political change in Russia to repeat all the mistakes of the 1990s by accepting Russia as a trusted partner without conducting any demilitarisation or democratisation attempts in the country. For Ukraine, it will significantly increase the risks of a new war with Russia, who will be perceived as an equally democratic country by the West, and, therefore, will be again granted a right to participate in the system of international trade, security etc.

A third scenario envisions Russia’s dissolution and, subsequently, a substantial reduction of its aggressive potential. This scenario does not entail that all newly emerged countries would be free from imperial ambitions or would qualify as liberal democracies. However, and most important, their possibilities to wage full-scale wars would be significantly reduced due to a population decline from 140 million to 20-50 million people in each country and their nuclear disarmament, among other factors. Even a potential Russia’s legal successor, the most aggressive country of Muscovy, with the population of some 40-60mn people, which is less than current Poland and Ukraine combined, and without nuclear weapons, would not risk to attack Ukraine and would have to curb its ambitions.

Therefore, Ukraine’s strategic interests should lay in the acceleration of Russia’s dissolution into several independent countries and their subsequent re-integration into the global security architecture. The fall of the Russian empire is not expected to proceed rapidly. However, Ukraine could already demonstrate that such secessionist movements in Russia would receive international support, for instance, in the format of recognition of their statehood, or to provide a platform for healthy debates, including among academics, about their nation state-building.

This article was orinigally published in Ukrainian by Tyzhden.Ua

Did you like this article? Donate and support the European Resilience Initiative Center: