Vindicating Global Security: Can the UN still be a Gamechanger?

In 1994 Ukraine joined the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), and gave up the third-largest nuclear weapons stockpile in the world. In exchange, Ukraine received security assurances (or security guarantees, as called in the Russian- and Ukrainian-language versions of the document) from the US, Russia, and the UK. The agreement was titled the Budapest Memorandum.

A decade and a half later, one of these guarantors, Russia turned into a nuclear weapon-blackmailing threat for Ukraine and the world, responsible for politically-motivated murders, genocide, mass war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Nevertheless, Russia continues to enjoy its permanent member benefits of the UN Security Council (UNSC), including the power to veto UNSC security and defense-related decisions. This country today presides upon the only international organization body, the UNSC, that is responsible for global peace and security and has a right to authorize international military interventions against any aggressor country. The demand to critically revise existing international institutions, responsible for the global security architecture, has never been more pressing.

An Abandoned Nuclear Missile Silo in Ukraine. Photo: Michael, CC-BY-3.0

Does Russia even belong to the UN Security Council?

It might sound counterintuitively, but Russia has no legal rights for a UN membership, let alone a permanent member seat at the UN Security Council. Russia’s UN membership is, arguably, the biggest swindle in the history of international politics. Why was this situation tolerated for over three decades?

Article 4 of the UN Charter provides that new countries must be admitted to the UN by a General Assembly vote.1 After the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, Russia claimed to have inherited the membership of the newly-defunct USSR, what effectively stripped Russia off an obligation to go through a voting procedure. But Russia has never officially submitted this claim for the UN to evaluate.

From a point of view of international law, even the very assertion of Russia’s inheritance of USSR legal rights is inaccurate. On December 26th 1991, the Supreme Council of the USSR declared that "the USSR as a state and as a subject of international law ceases to exist".2 This means that none of the states which appeared on the territory of the dissolved Soviet Union was therefore a legal successor of the USSR. Russia was just one of these new states, and did not inherit any privileges. Moreover, with exception of Ukraine and Belarus, who had been the signatories of the UN Charter ab initio since 1945, all of these new countries have gone through the UN General Assembly voting procedure. Russia, in violation of the logic of law, simply changed its nameplate from the USSR to Russian Federation. Hence, legally speaking, Russia has never been admitted to the UN by a mandatory General Assembly procedure, what should make Russia’s membership in the UN and a permanent member seat in the UN Security Council null and void.

UNSC Voting on DPRK in 2005. Photo: UN, CC-BY-4.0

Such illegitimate membership of Russia in the UNSC has its advantages for the country. The UNSC has a unique right to impose collective measure against an aggressor country. Such sanctioning can be vetoed by any UNSC permanent member, including Russia itself. This effectively provides Russia with immunity against any UNSC collective measures, which Moscow continues to abuse. In return, the UN has to bear all brand damage costs caused by Russia, such as undermined effectiveness, authority, and legitimacy of the UNSC. Is there a way to remedy this situation?

Can Russia be disciplined?

The UN unwillingness to discipline Russia and to disprove its earlier inability to react rests purely on the international organization’s leadership. Especially taking into account that the strategy to expel Russia from the UNSC is well-known. Under Rule 17 of the Council's provisional rules of procedure “[a]ny representative on the Security Council to whose credentials the Security Council has made a challenge shall continue to participate in the meeting with the same rights as other representatives until the Security Council has decided the matter”.3 This means that the former member countries of the Soviet Union have a legal means to challenge and, if successful, to fully undermine Russia's status as a permanent member of the UNSC.

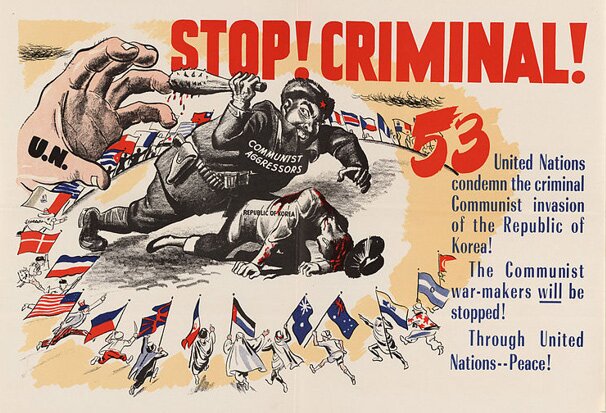

"Stop! Criminal!" a Cold War poster cheers the UNSC decision to impose collective measures against the Soviet Union in Korean War.

This is how such a theoretical scenario could be implemented in practice. First, Ukraine could appoint a diplomat to the USSR seat of the UNSC. Russia's representative will likely object this move, and, under abovementioned Rule 17, Russia's representative would likely to "continue to sit" on the Council until the Council voted on the matter.

Such voting on an objection to the credentials of a Security Council representative must be decided by the vote of nine UNSC members, independently of the permanence of their UNSC status, according to UN Charter Article 27 (2), and using the Council's Provisional Rules of Procedure as the legal basis. 4 The most important part is that, contrary to other UNSC votings, procedural matters are not subject to a veto power under UN Charter Article 27(2).5 Hence, neither Russia, nor its unlimited friend China are able to veto such a credentials voting to secure Russia’s UNSC seat.

If nine UNSC members vote against Russia’s continued UNSC permanent membership, on the basis that Russia never fulfilled the criteria of Charter Article 4(1), then Russia’s representative will have to vacate the USSR seat. Subsequently, a Ukrainian representative (or a representative from another country emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union) will take this seat. Voila! The revolution has succeeded; justice has been restored.

USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev addressing the UN General Assembly in 1988. RIA Novosti archive, image #828797 / Yuryi Abramochkin / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Justice vs. Practicality

Nevertheless, not every country seems to favor justice when offered to establish a historical precedent that might put its own position at risk in the future. The UNSC heavyweights are rather skeptical about possible consequences of such a move. Hence, the UNSC political willingness and public pressure are just as important to achieve the goal of Russia’s expulsion from the UNSC, as the legal justification of such a process.

This is why a group of Ukrainian members of the parliament has launched an #unrussiaUN advocacy campaign in 2022.6 In October, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe recognized Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism and called for the UN General Assembly to “look into” the compatibility of a UNSC permanent member status with Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, while noting an “increasing support for a reform” of the UNSC.7 Charles Michel, a president of the European Council, even openly called for Russia's expulsion from the UNSC on the grounds of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This demand was supported by other leaders, including US President Biden and French President Macron, who also called on limiting the UNSC veto right due to the Russian aggression. The campaign culminated in the Ukrainian parliamentary resolution adopted on December 1st, 2022, which recognized the illegitimacy of Russia's membership in the United Nations and called to reform the international organization.8 It is now up to the UN to define its path that would differ the modern-day international organization from the 20th-century League of Nations.

Conclusion

Russia's history of violence and impunity did not start in the 20th century. However, its current modus operandi is deeply rooted in its illegitimate membership in the UN and a permanent member seat in the UNSC. The UN must finally do its job and provide peace and security to its all members. This could be done only if a war crime perpetrator is punished and is obliged to compensate damages caused by its aggression. The likelihood of such outcome with Russia maintaining its UNSC permanent member status is questionable. Doesn’t it make the UN questionable as well? Let’s prove otherwise. A path to restoring security has never been clearer.

Did you like this article? Donate and support the European Resilience Initiative Center:

1. UN Charter Article 4 https://legal.un.org/repertory/art4.shtml

2. https://rg.ru/2021/12/25/deklaraciia-v-sviazi-s-sozdaniem-sodruzhestva-nezavisimyh-gosudarstv.html

3. United Nations Security Council Provisional Rules of Procedures, Rule 17 https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/rop/chapter-3

4. UN Charter 27(2) https://legal.un.org/repertory/art27.shtml

5. UN Charter 27(2) https://legal.un.org/repertory/art27.shtml

6. Compare: https://uscc.org.ua/en/unrussiaun/

7. https://pace.coe.int/en/files/31390/html

8. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2787-20#Text