Russia's Mine-Contaminated Path to War Crimes

In 2004, Russia’s President Putin signed the parliament’s ratification of the Protocol II to the 1980 Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW).1 Russia accepted obligations restricting its use of mines, booby-traps and similar devices as a means to protect civilians from indiscriminate weapons.2 Violations of these obligations such as failing to map the exact locations of mines and booby-traps laid out in a conflict zone, constitute a war crime.3

Russia is also responsible for mine-related war crimes committed by Ukraine's DPR and LPR militias since 2014. In January 2023, the European Court of Human Rights issued an interim ruling determining that Russia had begun its military agression against Ukraine in its eastern regions no later than in August 2014.4 The ruling also confirmed that Ukrainian territories, occupied by DPR and LPR militias, had been effectively under the jurisdiction of Russia starting from 2014. Hence, this court decision set a starting point of Russia's war crimes committed against Ukraine not in 2023, but already in 2014.

A map of Ukraine’s mine contamination

Prior to Russia’s invasion in February 2022, Ukraine ranked third in the world for the number of accidents associated with anti-vehicle mines and forth for the number of casualties from mines and so-called explosive remnants of war (ERW).5 The 2014-2022 Russia-backed Donbas military conflict contaminated approximately 8% of Ukrainian territory. This conflict alone turned eastern Ukraine into one of the largest mine-polluted areas in the world and put two million residents at risk.6 Russia’s full-scale invasion of 2022-2023 has re-contaminated the Donbas conflict zone and is believed to have increased the total mine- and ERW-contaminated territory of Ukraine to 30%.7 As Ukraine is the second largest European country, this mined territory already exceeds twice the size of Austria. It is likely to take decades of humanitarian demining to make this land safe for human use.

“It is a massive scale. In areas like we were, in Balakliya or Izyum [Kharkiv region], the density of minefields is unreasonable. It feels like someone had a tremendous number of mines to lay, and they decided to use them all. I have never seen anything like that, not even in Syria, despite the comparability of conflicts. I have never seen that in Donbas before, either,” explains Yuliia Chykolba, an explosive ordnance risk education manager at HALO Trust.

Russia’s military invasion proliferated its mine-polluting metastases from the Donbas conflict zone to Ukraine’s northern and southern regions. What’s more is the ERW contamination that spread through all territories affected by military fighting. Out of 27 Ukrainian regions, only two – Zakarpattia and Chernivtsi – could be considered low-ERW-contaminated territories having sustained only a handful of Russian strikes. Still, Ukraine’s State Emergency Service warns: a high probability of detecting explosive objects exists on the entire territory of the country.

An interactive map of potential mine hazard in Ukraine. Source: Ukraine’s State Emergency Service8

Humanitarian demining profile

Russian landmines in Ukraine are scattered across civilian areas in a haphazard and disorganised fashion.9 Some areas, where Russian troops lacked time and/or professional expertise to thoroughly mine the surroundings, are relatively accessible. Kyiv region is one of these areas. There, Russian troops only had time to lay anti-vehicle landmines as defence fortification lines before being forced to withdraw by Ukrainian forces.10 Consequently, Kyiv region became one of the earliest footholds for humanitarian demining.

The longer the Russian forces occupied an area, the more complicated the demining profile became. Ukraine's Donbas territories, partially occupied by Russia since 2014, are filled with unexploded ordnances and anti-personnel mines.11 Russia has never ratified the international Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, banning the use of such mines in conflicts due to the indiscriminate character of their impact, and did not hesitate to supply them to Ukraine's DPR and LPR militias.12 Since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Chernihiv region is saturated with Russian anti-personnel and anti-vehicle landmines, booby traps, mines attached to toys, household equipment, human and animals corpses.13 Additionally, there are tonnes of ERW: projectiles, cluster munitions, remnants of high-tech western weapons systems, remnants of thermobaric weapons, wreckages of explosive drones.14 Similar challenges are expected in recently liberated areas, such as Kherson region, but they are yet to be assessed by humanitarian deminers.

“There is often a little bit of a pause between when areas have been liberated by the Ukrainian army before we can go in safely as a humanitarian actor and start demining. We have to be sure that we are not putting our staff at risk. Therefore, front line areas we wouldn’t be demining because of an artillery threat. If it is so close to a front line, there is also a risk of the line shifting and the area being re-contaminated,” tells Mairi Cunningham, Programme Manager, Ukraine, at HALO Trust.

Implications of Ukraine’s mine contamination

Since February 2022, the HALO Trust recorded 313 accidents related to mine and ERW detonations in Ukraine. These accidents, almost half of which were caused by anti-vehicle mines, killed 168 people and injured 379. The risk of mine and ERW detonations will continue to grow as the Ukrainian people seek to return to their normal lives. This dynamic has already been demonstrated in the Donbas conflict zone: the number of mine casualties has been progressively increasing up to 2,000 casualties in 2014-22.15

Landmine and ERW-contamination denies access to agricultural fields, roads and rural paths and turns farming into a high-risk activity. At least 56% of Ukrainians are estimated to own farm plots of up to 500 acres. They produce 30% of the crops and up to 50% of the livestock-related commodities.16 Landmine casualties will affect agricultural production with an aggravating impact on the individual wellbeing, state budgetary recovery and international agriculture trade.17

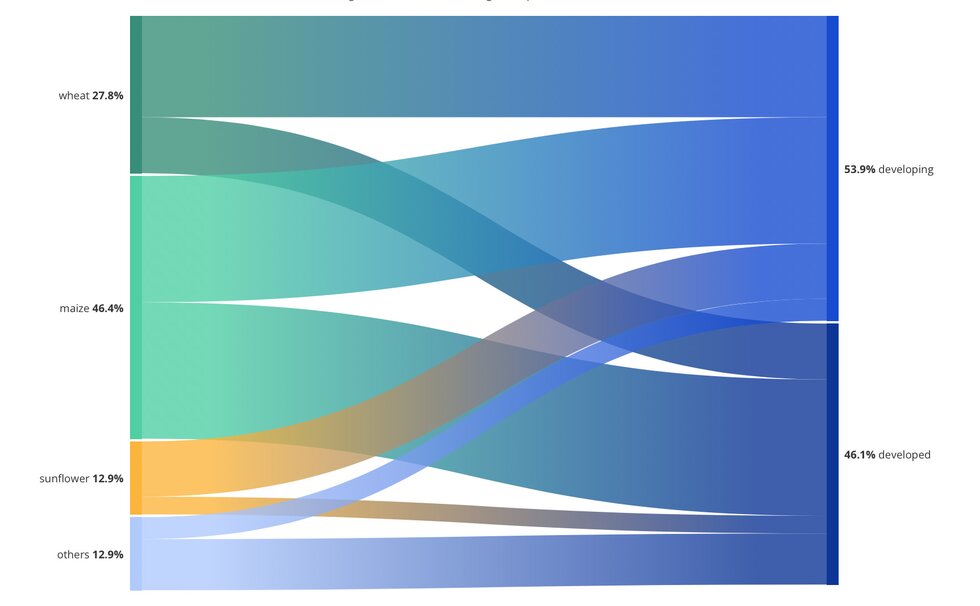

Prior to Russia’s invasion, Ukraine, one of the world’s largest grain exporters, supplied 45 million tonnes of grain annually to the global market.18 As Russian troops seized control over Ukraine’s coastal territories, Ukraine was forced to suspend its agricultural exports.19 This drove the international price of wheat up by 70% in two weeks.20 After a five-month Russian military blockade, Ukraine partially resumed foodstuff shipping and, as of January 2023, exported 18 million tonnes of agricultural commodities, including to famine risk areas in Kenya, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Yemen, Ethiopia, and Somalia.21

Ukraine’s agricultural exports by commodity and destination. Source: The Council of the European Union22

Ukraine is likely to keep reducing food exports in the coming seasons.23 Landmine and ERW-contaminated agricultural fields require large-scale humanitarian demining operations. Such a strategic approach to demining in Ukraine is hindered by its competition with the war effort for resources. An alternative for Ukraine, and a way-out from war crimes accusations for Russia, is suggested in the CCW’s Protocol II. Its article 10 requires a state party to provide “technical and material assistance” for de-mining operations in territories it has contaminated.24

This article has been originally published under the title "Eine solche Minenbelastung habe ich vorher noch nie gesehen"

Bibliography:

1. Russia's Presidential Administration. (2004, December 13). Russia's ratification of the Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 (Protocol II to the 1980 CCW Convention as amended on 3 May 1996). Szrf.ru.

2. International Humanitarian Law Databases. (1996, May 03). Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 (Protocol II to the 1980 CCW Convention as amended on 3 May 1996).

3. International Humanitarian Law Databases. (1996, May 03). Article 9 - Recording and use of information on minefields, mined areas, mines, booby-traps and other devices.

4. European Court of Human Rights. (2023, January 25). Eastern Ukraine and flight MH17 case declared partly admissible.

5. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2022, April 4). International Mine Awareness Day: How do mines impact refugees and idps?

6. Ostanina, E. (2018, July 17). Landmines in the Donbass conflict zone: Threats for the population and the necessity of mine clearance. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Ukraine. Country report. Landmine & Cluster Munition Monitor. (2021, February 22).

7. Wordsworth, R. (2022, December 21). Russia has turned Eastern Ukraine into a giant minefield. WIRED UK.

8. Ukraine’s State Emergency Service. (n.d.). Ukraine's Mine Clearance.

9. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2022, November 10). Clearing the Mines 2022 Report. ReliefWeb.

10. Clearing landmines and other debris of war in Ukraine. The HALO Trust. (2022).

11. Ostanina, E. (2018, July 17). Landmines in the Donbass conflict zone: Threats for the population and the necessity of mine clearance. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.

12. Ibid.

13. Balachuk, I. (2022, March 8). Civilian car blown up by Russian mine in Chernihiv region: 3 adults dead, 3 children wounded.

Rukomeda, R. (2022, April 27). 'Russian mines are a big crime against Ukraine and humanity'. Euractiv.

14. Removing Explosive Remnants of War in Ukraine. DRC Danish Refugee Council. (2022, September 23).C

Clearing landmines and other debris of war in Ukraine. The HALO Trust. (2022).

15. Losh, J. (2017, November 18). Land Mines in Ukraine's east put it among world's most dangerous areas for civilians. The Washington Post.

Flint, J. (2021, December 7). As war devastates Ukraine, AOAV examines the country's existing landmine problem. Action on Armed Violence.

16. Griffiths, C. (2022, May 12). Ukrainian farmers Dodge Landmines and rockets as World's farmers offer help. AgWeb.

17. OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine. (2019, December). The impact of mines, unexploded ordnance and other explosive objects on civilians in the conflict-affected regions of eastern Ukraine. Organization for Security and Co-peration in Europe | OSCE.

18. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2022, September 16). The Black Sea Grain Initiative: What it is, and why it's important for the world.

19. The New York Times. (2023, January 25). Maps: Tracking the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

BBC News. (2022, November 14). Ukraine in maps: Tracking the war with Russia.

20. Cooper, A. (2022, July 22). Wheat prices drop to pre-war levels after Ukraine and Russia strike deal to unblock shipments.

21. United Nations. (2022, November 17). Black Sea Grain Initiative | Joint Coordination Centre.

The Black Sea Grain Initiative: Food Security. U.S. Agency for International Development. (2022, December 5).

United Nations. (2023, January 18). Un aims to boost aid to frontline areas of Ukraine; Black Sea grain exports near 18 million tonnes. UN News.

22. The Council of the EU and the European Council. (2023, January 20). Ukrainian Grain Exports Explained.

23. Ukraine sees fall in 2023/24 grain exports on smaller sowing area. Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide. (2022, December 7).

24. International Humanitarian Law Databases. (1996, May 03). Article 10 - Removal of minefields, mined areas, mines, booby-traps and other devices and international cooperation