Russia’s “Conventional” Nuclear Threats Demand a UN Security Council Overhaul

Russia’s year-long conventional invasion of Ukraine has been accompanied with nuclear threats from its very beginning. In a purely militaristic method, Russia’s President Putin used the country’s nuclear weapons capabilities to seek to force Ukraine to compel to Russia’s political demands and to deter NATO from intervention. At the same time, Russia showed its innovative ability to use Ukraine’s civilian energy facilities as nuclear threats. This also demonstrated how deficiencies of the existing global nuclear governance architecture could enable terrorist-like behaviour of a UN Security Council (UNSC) permanent member.

By using the term “global nuclear governance architecture”, as opposed to “global nuclear security architecture”, this article aims to eliminate possible confusion between nuclear security as overarching stability of the nuclear security regime and a sub-field of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)`s activities that focuses on non-state use of nuclear technologies. This article follows J.Herbach in defining governance as “the combined impact of rules and expectations of conduct (substance), on the one hand, and institutional arrangements and process (organisation), on the other, which gives shape to and guides the behaviour of relevant actors in a given issue area.”1

“Conventional” nuclear threats

Russia’s conventional invasion of Ukraine multiplied the risk of nuclear accidents from the very first hours of the military incursion. On the 24th of February, 2022, Russia`s President Putin announced the start of a military invasion of Ukraine shortly before 6am Moscow time. Already at 6:41am, Russian troops have entered the territory of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant (NPP).2 Until that moment, no civilian nuclear power plant, operating or decommissioned, had ever been attacked or seized by a foreign army.3 Russia’s invasion of Ukraine became the first international military conflict that erupted amid multiple nuclear power programme facilities.

Locations of reported Russian attacks in the morning of the 24th of February, 2022. Source: Bloomberg reporting4

The Chornobyl NPP, located in the middle of a post-nuclear accident 30km Exclusion Zone, contains several decommissioned reactors and numerous radioactive waste management facilities. Immediately after Russia’s takeover of the power plant, Ukraine’s Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) recorded an increase in gamma radiation rate caused by the displacement of contaminated soil by heavy machinery.5 Two months later, satellite images revealed that Russia’s armed forces had stationed their troops in the most contaminated part of the exclusion zone, the “Red Forest.” Russian troops organized there a military campsite: bulldozers dug trenches and bunkers in contaminated soil, and soldiers set up a camp fence using sandbags, filled with local sand.6 Spring wildfires, erupted in the exclusion zone, blew dust along the camp site and roads used by troops to redeploy their military equipment.7 The IAEA claimed that, although radiation levels exceeded the usual radiation level in this area by 3-5 times, this increase affected sparsely areas in the exclusion zone and did not pose risks to people.8 However, Ukraine reported that hundreds of Russian soldiers have experienced symptoms of acute radiation sickness.9 A subsequent investigation carried out by a Greenpeace team stated that their measurements of radiation levels were at least three times higher than those reported by the IAEA.10 In the end of March, Russia’s armed forces withdrew from the site and shortly thereafter abandoned its plan to capture Ukraine’s capital of Kyiv.

A week after capturing the Chornobyl NPP, Russia`s armed forces advanced in south-eastern Ukraine and seized control over a second Ukrainian nuclear power plant. The Zaporizhzhia NPP is the largest operating nuclear plant in Europe and generates about 20% of Ukraine`s electricity.11 Russia’s army advancement into the Zaporizhzhia NPP provoked fighting between Russian and Ukrainian troops. In parallel, Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom flew its senior technical representatives into the Zaporizhia NPP to seize administrative control over its energy infrastructure.12 In August 2022, the Russia-occupied Zaporizhzhia NPP again came under multiple military attacks, which both Ukraine and Russia blamed on each other.13 The plant has sustained infrastructure destruction caused by shelling, damage to its power lines, repeated power outages, and disconnection from the electricity grid as a result of shelling. The IAEA’s Director General Grossi has been attempting to negotiate the establishment of a demilitarisation zone around the NPP since August but so far without success. One possible explanation for Russia’s reluctance to agree to this proposal is its alleged use of the Zaporizhia NPP as a military base. Russia’s armed forces allegedly moved military equipment, explosives, and weapons to the NPP’s engine rooms.14

During the first months of Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine, Russian troops also shelled smaller Ukrainian nuclear facilities across the country on multiple occasions. Only in February-March 2022 Russia’s armed forces shelled the offices of the radioactive sources operators in Kharkiv and Mariupol, the radioactive waste management facilities Radon in Kyiv and Dnipro, the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology hosting the subcritical Neutron Source installation.15 The character of Russia’s attacks on Ukraine’s nuclear energy infrastructure demonstrates that these facilities were likely deliberately targeted by Russian troops. These attacks also resulted in the stealing of Ukrainian radioactive sources, which, as the IAEA estimates, might re-emerge on a black market.16 A year after the beginning of Russia’s invasion, its armed forces continued to occupy Ukraine’s Zaporizhia NPP. This continuing “conventional” nuclear threat demonstrates the need to overhaul the existing global nuclear governance architecture and, most importantly, the UN Security Council.

Global nuclear governance architecture

Russia’s military attacks on, and capture of, Ukraine`s nuclear energy infrastructure have revealed deficiencies in the existing global nuclear governance infrastructure developed in the aftermath of World War II. One of them is the notion that a UN Security Council permanent member would never engage in behavior traditionally thought to reflect the modus operandi of a terrorist organization.

In international relations, separation of state- and non-state actors got cemented in the aftermath of World War II. A still growing network of international and inter-governmental organizations, largely operating under the UN umbrella, pursued the major goal of maintaining international peace and security by developing international cooperation among countries. At first, such a state-centric approach to international cooperation and, particularly, international security left non-state actors behind the scope of work of international organizations (IOs). However, the proliferation of non-state actors, such as non-governmental organizations, private companie,s, terrorist organizations, political movements, etc., has forced IOs to accommodate their growing sense of agency. Still, nation-states refused to treat such actors as equal and limited their political involvement at the international level. To this day, IOs continue to build administrative, legal and operational barriers separating nation-states and non-state actors.

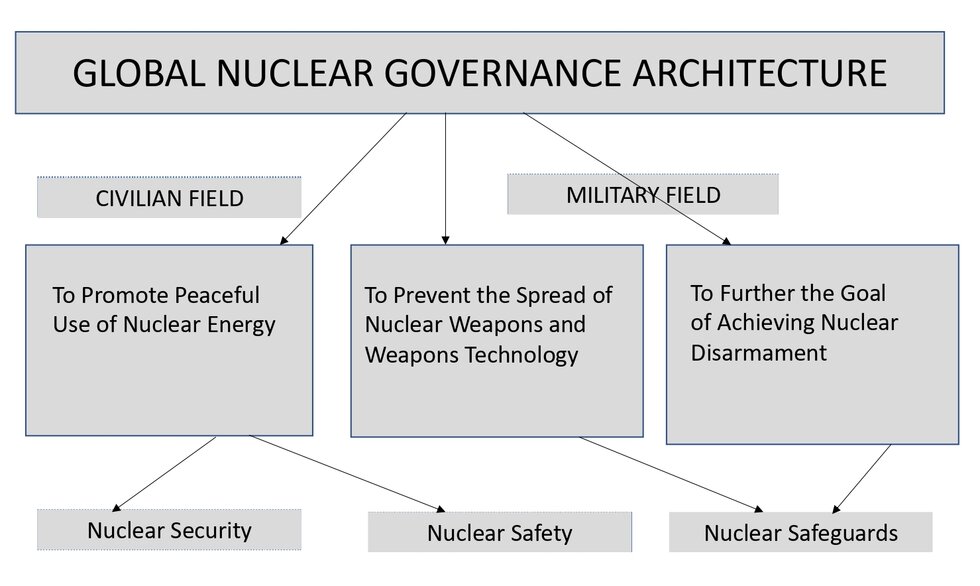

In nuclear security, the US Atom for Peace initiative and the subsequently launched work of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) cultivated the same principle of the risk separation between nation-states, who enjoy the legitimate monopoly over the means of violence, and non-state actors. The current global nuclear governance architecture limits state-posed nuclear security risks mostly to illegal development of nuclear weapons, while non-state criminal and terrorist groups are suspected of theft, sabotage or other malicious acts. However, the nuclear field presents a unique dilemma of the dual-use nature of nuclear energy, when the same materials, processes and technologies might be used for both peaceful and military-related applications.17 This interconnectedness of the nuclear civilian and military applications of nuclear energy led to the artificial separation of the global nuclear governance architecture into three domains: nuclear safety, nuclear security and nuclear safeguards. Largely promoted via the IAEA, this framework conceptualises the following definitions of the nuclear governance domains:

Nuclear Safety focuses on “the protection of people and the environment against radiation risks"Nuclear Security concerns with “the prevention of, detection of, and response to criminal or intentional unauthorised acts involving or directed at nuclear or other radioactive material, associated facilities, or associated activities”Nuclear Safeguards provides “a set of technical measures through which the IAEA verifies that states are honouring their international legal obligations to use nuclear material and technology only for peaceful purposes.”18

The IAEA's Global Nuclear Governance Architecture

Russia’s seizure of territorial and administrative control over Ukraine’s NPPs highlighted an IAEA blind spot: acts of “nuclear terrorism” conducted by nation-states, such as stealing of nuclear materials.19 However, it was not the first time when a deficiency of the IAEA’s approach to the global nuclear governance architecture got unveiled. In 2010, a Stuxnet cyber malware, a cyberattack on Iran's nuclear facilities, disrupted the work of uranium enrichment facilities in the country and is believed to delay its nuclear programme by months.20 Similarly to Russia, the IAEA could not better address Iran’s illicit nuclear weapons development programme due to its state-centric approach dismissive of any notion of nuclear terrorism of nation-states.

A UN Security Council overhaul

The example of a cyber malware against Iran’s illicit nuclear weapons programme is not a suggestion to respond to Russia’s military attacks on, and seizure of, Ukraine’s NPP with a cyber offensive. As demonstrated by dynamics around Iran’s Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, this measure is unable to sustain the positive outcome in the long run. Systemic challenges, presented by Iran and Russia to the global security order, require a formulation of an international collective security framework that is inclusive, proactive, and accountable.

What stops the international community from introducing such a change is the UN Security Council. In the aftermath of World War II its composition, consisting of five major international powers who had withstood military aggression of the Axis alliance, seemed reasonable and balanced by an equally distributed veto right in light of the remaining political differences. The absence of a legally envisioned reforming mechanism also aimed at preventing one UNSC permanent member from subjugating others. These qualities nowadays are seen largely as damaging, as they block any attempt to further improve the global collective security system. Within the last 70 years, the UN SC turned to be seen as an exclusive, oligopolistic body, unable to share its power and keen on vetoing any opposing initiative, representing the largest remnants of imperialist hegemony. The existing global collective security framework grants the UNSC permanent members the exclusive rights to adopt internationally binding resolutions and to decide on the use of collective force against a threat to international peace and security. No legal mechanisms currently exist to challenge an individual UNSC decision, not to mention to discontinue this imperialistic practice of maintaining regional spheres of influence.

The UN Security Council requires an overhaul. There are already plenty of reform proposals on the table: a transformation of the existing organisation, a forced dissolution of the UN, or even the establishment of a competing international agency. Reforming the UNSC will require political will and long-term efforts from all parties, seems hardly attainable in the current environment of deficient political consensus. Nevertheless, the change, ensuring that no country has a veto right to continue committing war crimes against civilians, needs to happen as soon as possible.

Bibliography:

1. Herbach, J. (2021). In International Arms Control Law and the Prevention of Nuclear Terrorism (p. 29). Edward Elgar Publishing.

2. Grossi, R. M. (2022, April 28). Nuclear Safety, Security and Safeguards in Ukraine. Summary Report by the Director-General 24 February - 28 April 2022. International Atomic Energy Agency.

3. Ibid.

4. Russia-Ukraine War Timeline: Maps of Russia's Attacks. Bloomberg.com. (2022, February 18).

5. Grossi, R. M. (2022, April 28). Nuclear Safety, Security and Safeguards in Ukraine. Summary Report by the Director-General 24 February - 28 April 2022. International Atomic Energy Agency.

6. Brumfiel, G. (2022, April 7). Satellite Photo Shows Russian Troops were Stationed in Chernobyl's Radioactive Zone. National Public Radio. Retrieved 2023.

7. Kramer, A. E., & Prickett, I. (2022, April 8). Russian Blunders in Chernobyl: 'They Came and did Whatever They Wanted'. The New York Times.

8. Grossi, R. M. (2022, April 28). Nuclear Safety, Security and Safeguards in Ukraine. Summary Report by the Director-General 24 February - 28 April 2022. International Atomic Energy Agency.

9. Nadeau, B. L. (2022, March 31). Russian Troops Suffer 'Acute Radiation Sickness' After Digging Chernobyl Trenches. The Daily Beast.

10. Greenpeace Investigation Challenges Nuclear Agency on Chornobyl Radiation Levels. Greenpeace International. (2022, July 20).

11. Russia-Ukraine War Timeline: Maps of Russia's Attacks. Bloomberg.com. (2022, February 18).

12. Grossi, R. M. (2022, April 28). Nuclear Safety, Security and Safeguards in Ukraine. Summary Report by the Director-General 24 February - 28 April 2022. International Atomic Energy Agency.

13. Davenport, K. (2022, September). Attacks on Ukrainian Nuclear Plant Intensify. Arms Control Association.

14. Russians placed military equipment and ammunition at the Zaporizhzhia Npp. (2022). YouTube.

15. Grossi, R. M. (2022, April 28). Nuclear Safety, Security and Safeguards in Ukraine. Summary Report by the Director-General 24 February - 28 April 2022. International Atomic Energy Agency.

Russia Shelled the Radioactive Waste Disposal Site of Kyiv Radon Association. Ukraine Crisis Media Center. (2022, February 27).

16. Grossi, R. M. (2022, April 28). Nuclear Safety, Security and Safeguards in Ukraine. Summary Report by the Director-General 24 February - 28 April 2022. International Atomic Energy Agency.

17. Herbach, J. (2021). In International Arms Control Law and the Prevention of Nuclear Terrorism (p. 33). Edward Elgar Publishing.

18. Scherer, C. P., & Rothrock, L. G. (Eds.). (n.d.). In Introduction to Nuclear Security (pp. 25–26). INSEN Textbook Series.

19. Stone, R. (2022, March 25). Dirty Bomb Ingredients Go Missing from Chornobyl Monitoring Lab. Science.

20. Davenport, K. (2022, September). Attacks on Ukrainian Nuclear Plant Intensify. Arms Control Association.