Looting, Stealing, Destroying: How Russia Weaponized Art Theft

Throughout the history of Ukrainian-Russian relations, the physical atrocities have always been complemented by eradicating the Ukrainian identity. To this end, Moscow imposed its influence by repressing Ukrainian intelligentsia, banning the Ukrainian language and assimilating its grammar, appropriating Ukrainian artists and stealing their artworks. A centuries-long attempt to erase Ukraine as a nation and a sovereign country from geographical and mental maps has culminated in the ongoing war of extinction called by the Russian propagandist de-ukrainization.1,2

To achieve its goals, Russia weaponises culture. Looting artworks during the war is a common practice prohibited under international law, particularly by the 1954 The Hague Convention for the protection of cultural property in armed conflicts.3 Prior to and during WWII it was common that by capturing cultural heritage the invading army could either pursued material goals, while not always capable of comprehending the actual price of cultural objects, or tried to gain soft power for the aggressor state. In Ukraine, Russia is targeting the cultural heritage that can embody the long-time history of Ukraine as a cultural entity. The physical presence of Ukrainian cultural objects in Russian museums helps Russia rewrite the narratives around historical events to present Ukraine as part of Russia and call Ukraine's history to be fiction.

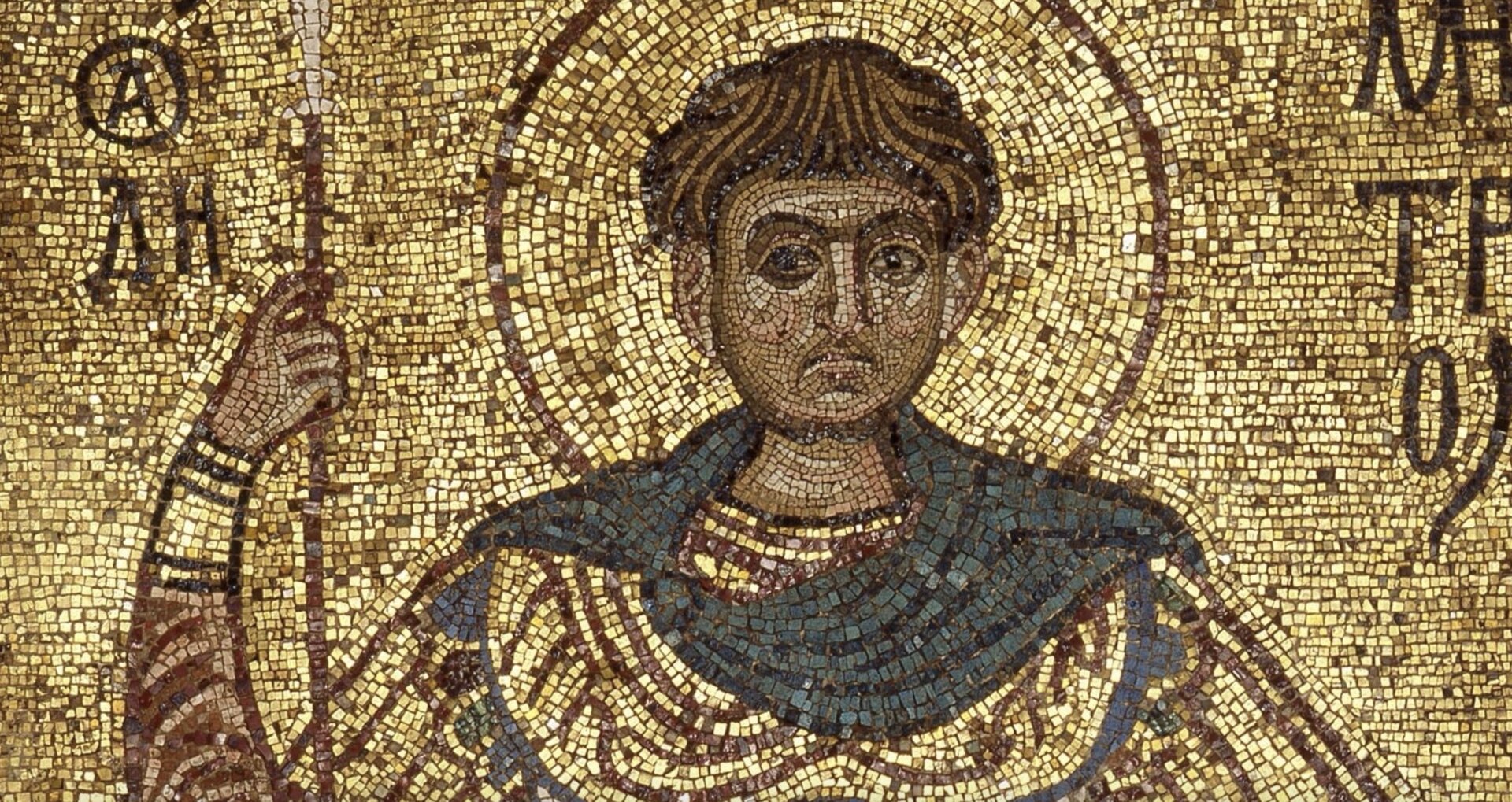

St. Dmytro of Solun. Mosaic from Kyiv St. Michael Cathedral, looted and transferred to Moscow Tretyakov Gallery after the Cathedral's demolition in 1930s.

The Scythian Gold Saga

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has challenged international law that aims at protecting and preserving cultural heritage in dire circumstances of armed conflicts. Since 2014, Ukraine has been in a complicated legal dispute with Russia concerning the collections of Scythian gold, colloquially known as Crimean treasures. Just a month before Russia illegally invaded the Crimean Peninsula, the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam hosted the exhibition Crimea. Golden Island in the Black Sea, dedicated to the ancient history of Crimea. It featured 19 exhibits from the Kyiv Museum of Historical Treasures, a branch of the National Museum of History of Ukraine in Kyiv, and 565 exhibits from four Crimean museums.4 The collection included gold and ceremonial daggers used by the nomadic tribe, a golden helmet from the 4th century BC, amulets, jewellery, and other treasures.5

After the annexation of Crimea, Russia pressed the Netherlands to send the exhibits back to the Russia-controlled Crimean museums. In its turn, Ukraine insisted on Ukrainian ownership of the collection exhibits, as they belonged to the State Museum Fund of Ukraine. The first decision of the Amsterdam district court in 2016 determined that the Dutch museum must hand over the disputed objects to Ukraine. The court ruling was based on the 1970 UNESCO Convention and defined the central role of state authorities in international art loans.6 The judgment also proved that the Allard Pierson Museum acted rightfully by storing the objects until the final verdict.7 The gold should have remained in the Dutch museum's stores pending an appeal. Ukraine was required to cover the storage and insurance costs to preserve the collection. As expected, Crimean museums acting in the interests of Moscow appealed the ruling.

Scythian golden helmet. Photo by the Ukrainian Museum of Cultural Valuables.

Only in October 2021, the Amsterdam Court of Appeal ruled in Ukraine's favour. The collection should be returned to the Ukrainian state "until the situation in Crimea has "stabilised".8 In January 2022, a month before the full-scale Russian invasion and on the last possible day, Crimean museums filled the appeal again. The Supreme Court of the Netherlands has scheduled a court session to take a final decision for the 15th of September, 2023.9

Weaponisation of Culture

However, Russia’s pursuance of stealing ownership of Ukraine’s collections of Scythian gold is not the only example of Russia’s looting Ukrainian cultural heritage. As of 2016, Ukraine lost control over 99 museums, following Russia’s occupation of Crimea and the parts of Luhansk and Donetsk regions. Ukraine’s estimated losses ranged between one and two million cultural objects.10 Following the full-fledged Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2022, the number of such lost cultural artifacts has skyrocketed.

In 2022, Russian troops stole Scythian gold artifacts from the Museum of Local History of Melitopol, a temporarily occupied city in Zaporizhzhia region. The collection comprised at least 198 gold objects, including gold plates, rare old weapons, 300-year-old silver coins, and special medals11. As art critic Charlotte Mullins noted:

"it is clear that Putin sees the Scythian gold as particularly central to Ukraine’s cultural identity and independence. It is not the first time he has tried to claim it for Russia. But these latest thefts are in keeping with Putin’s attempts to erase Ukraine’s independent history and promote his own expansionist model of a new Russian empire."12

Brian Daniels, who works with cultural workers at risk in conflict, explains Russia’s logic:

"There is now very strong evidence this is a purposive Russian move, with specific paintings and ornaments targeted and taken out to Russia. There is a possibility it is all part of undermining the identity of Ukraine as a separate country by implying legitimate Russian ownership of all their exhibits."13

A golden Scythian sword. Photo by the Ukrainian Museum of Cultural Valuables

After capturing Mariupol, Russia has reportedly stolen over 2,000 artworks from three local museums. The city council prepared evidence for Interpol to conduct a criminal investigation.14 Among the allegedly stolen works could be a handwritten Torah scroll, paintings by Arkhip Kuindzhi, Ivan Aivazovsky, Tetiana Yablonska, Ivan Marchuk, a bible from 1811, Orthodox icons, and 200 medals from the Museum of Medallion Art.

Three original works by the Ukrainian realist painter of Greek descent Arkhip Kuindzhi, a sketch titled Red Sunset and two preparatory works, Elbrus and Autumn Crimea, were reportedly stolen by Russians from the Kuindzhi Art Museum.15 The museum was destroyed in a Russian airstrike on the 21st of March, 2022. However, none of the three original Kuindzhi paintings were present in the building at the time of the bombing. Another detective story concerns the romantic maritime painter of Armenian origin Ivan Aivazovsky. Ukrainian Mariupol authorities reported that his original painting, The Coast of the Caucasus, was looted from the museum of Mariupol.16 The Russian side also reported the “temporary transferring” of one of Aivazovsky’s works to the local history museum in occupied Donetsk.17

'Elbrus' by Arkhyp Kuindzhi (1900).

These theft cases demonstrate a Russian behavioral pattern. Both painters were born and lived in modern-day Ukraine, Aivazovsky in Feodosia, Crimea, and Kuindzhi in Mariupol, Donetsk region. In their lifetime, both cities were under the Russian Empire's rule. Since 2014 and 2022, respectively, Russian forces have occupied the cities. Russia's policy of cultural appropriation created a reality, in which cultural institutions across the globe designated both painters as Russians, while ignoring their complex identities. Since 2022, museums worldwide have started reconsidering their approach.18

The looting was not a random plundering for the sake of enriching individuals. Witnesses say that the operations were expert-led, centrally controlled, and well-organised with the help of the Russian army. Scythian gold artifacts were allegedly extracted from the Melitopol museum by "a man in the white lab coat, using tweezers and special gloves". Russian soldiers with guns stood behind, watching around in case anybody would try to prevent a robbery.19

Russian looting from the Kherson Art museum. Photo from Kherson Art museum's facebook account

Compensations for Russia’s Museum Looting

The actual number and items of stolen art pieces are still to be estimated, which makes the restitution process even more complicated. Ukrainian museum employees have already identified some of the works based on photos taken in a museum storage in Simferopol, Crimea.20 The digital archive of the Kherson Art Museum preserves data about 14 000 artworks, including the paintings of Mykola Pymonenko, Ivan Aivazovskyi, Zinaida Serebriakova, August von Bayer, Mikhail Vrubel, and others. Alina Dotsenko says that up to 80% of the collection could be lost. The same destiny happened to the Kherson Museum of Local Lore. Before the invasion, its collection consisted of more than 170,000 exhibits: weapons, Scythian gold, ancient steels, amphoras, herbarium, and others. Russians left the rooms of the museums almost empty. Some stolen objects were already noticed in Henichensk, a temporarily occupied town in Kherson region.22

The liberation of the Ukrainian territories will not result in automatic immediate return of cultural treasures, particularly as there is no confirmed information of their current whereabouts. In most cases, the exact lists of stolen artifacts are also unclear. In 2014-2015, all the museums in the annexed Crimea were "nationalised" by Russia. The collections in the occupied parts of the Donbas region were allegedly transferred to Russia. As Russia has demonstrated on multiple occasions, the artworks could end up in museums across Russian borders, such as the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg and the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

'The Red Sunset" by Arkhyp Kuindzhi (1905)

Although the ideological purpose seems to be the primary purpose of mass plundering, some artifacts could re-emerge in the hands of private collectors or on the black market. Recently, the International Council of Museum (ICOM) published the Ukraine Edition of the Red List of Cultural Objects at Risk to assist collectors and institutions in identifying the stolen cultural objects.23 The list comprises 53 types of objects in seven categories, including span archaeology, books and manuscripts, numismatics, folk, religious, applied and fine arts. It is important to note that the list does not depict the actual stolen items but only serves to illustrate the categories of cultural goods that are the most vulnerable to illegal traffic.24

Based on experiences from previous armed conflicts, several international documents were developed to regulate the illegal trade of artworks from the places affected by armed conflicts. However, as in other spheres of international law, the regulations require updates in light of the scale and nature of the Russian attack against Ukrainian culture. Furthermore, the legal recognition of Ukrainian ownership over these cultural artifacts could take decades. The longer it takes, the more difficult it would be to find the looted cultural artifacts, examine their origins, background and owners, and to prove their belonging to the Ukrainian people, who understand their cultural and historical meaning.

Did you like this article? Donate and support the European Resilience Initiative Center:

1. Что Россия должна сделать с Украиной. РИА Новости https://ria.ru/20220403/ukraina-1781469605.html

2. Justification of genocide: Russia has openly declared its desire to exterminate Ukrainians as a nation. UA Crisis https://uacrisis.org/en/justification-of-genocide-russia-has-openly-declared-its-desire-to-exterminate-ukrainians-as-a-nation (English translation)

3. https://en.unesco.org/protecting-heritage/convention-and-protocols/1954-convention

4. “Crimea. Golden Island in the Black Sea. Chronicle of the struggle for the “Scythian gold” of Ukraine. Voice Crimea https://culture.voicecrimea.com.ua/en/crimea-golden-island-in-the-black-sea-chronicle-of-the-struggle-for-the-scythian-gold-of-ukraine/

5. Ukraine has legal right to Crimean artefacts, Dutch court rules. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/oct/26/ukraine-has-legal-right-to-crimean-artefacts-dutch-court-rules

6. Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/convention-means-prohibiting-and-preventing-illicit-import-export-and-transfer-ownership-cultural

7. Objects from Crimea to be returned to Ukraine. Allard Pierson Museum https://allardpierson.nl/en/news/objects-from-crimea-to-be-returned-to-ukraine/

8. Allard Pierson Museum has to hand over the Crimean Treasures to the Ukrainian State. De Rechtspraak https://www.rechtspraak.nl/Organisatie-en-contact/Organisatie/Gerechtshoven/Gerechtshof-Amsterdam/Nieuws/Paginas/Allan-Pierson-Museum-has-to-hand-over-the-Crimean-Treasures-to-the-Ukrainian-State.aspx

9. Advisory Opinion Advocate General to the Supreme Court: Court of Appeal’s decision can be upheld that the Allard Pierson Museum must hand over the Crimean Treasures to the State of Ukraine. Hoge Raad der Nederlanden https://www.hogeraad.nl/actueel/nieuwsoverzicht/2023/januari/advisory-opinion-advocate-general-to-the-supreme-court-court-appeal/

10. Зі щитом чи на щиті?: Захист культурних цінностей в умовах збройного конфлікту на Сході України. Українська Гельсінська спілка з прав людини https://www.helsinki.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Ukraine_kultura_13_09_Layout-1-1.pdf

11. Ukraine says Russia looted ancient gold artifacts from a museum. The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/30/world/europe/ukraine-scythia-gold-museum-russia.html

12. ‘Ukraine’s heritage is under direct attack’: why Russia is looting the country’s museums. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/may/27/ukraine-russia-looting-museums

13. Specialist gang ‘targeting’ Ukrainian treasures for removal to Russia. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/12/specialist-gang-targeting-ukrainian-treasures-for-removal-to-russia

14. Mariupol city council, Telegram-channel https://t.me/mariupolrada/9419

15. Росіяни знищили вщент Художній музей імені Архипа Куїнджі у Маріуполі. Локальна історія https://localhistory.org.ua/news/v-mariupoli-bulo-znishcheno-khudozhnii-muzei-imeni-arkhipa-kuyindzhi/

Mariupol city council, Telegram-channel https://t.me/mariupolrada/10235

16. Petro Andriushchenko, adviser to the mayor of Mariupol, Telegram-channel https://t.me/andriyshTime/513

17. В донецкий музей из Мариуполя передали картины Куинджи и Айвазовского. ТАСС

https://tass.ru/kultura/14518755?utm_source=google.com&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=google.com&utm_referrer=google.com

18. Музей Метрополітен визнав українцями художників Рєпіна, Айвазовського та Куінджі. Історична правда https://www.istpravda.com.ua/short/2023/02/13/162389/

19. Ukraine says Russia looted ancient gold artifacts from a museum. The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/30/world/europe/ukraine-scythia-gold-museum-russia.html

20. Херсонський художній музей, Facebook https://www.facebook.com/891757974215517/posts/5583903955000872/

Херсонський художній музей, Facebook https://www.facebook.com/art.museum.ks/posts/pfbid02m9R4H3r5ydKbcdzHYYyvVvxy2E77qeggzzX4xEa4EmPBgVp6DMStRncw7wNTjDxWl

21. Як виглядає пограбований росіянами Херсонський краєзнавчий музей. Фоторепортаж. Vgoru media https://vgoru.org/post/yak-viglyadaye-pograbovanij-rosiyanami-hersonskij-krayeznavchij-muzej-fotoreportazh

22. У Генічеській школі дітям показали вкрадені у Херсоні експонати музею. Геніченськ медіа https://henichesk.city/articles/268496/u-genicheskij-shkoli-dityam-pokazali-vkradeni-u-hersoni-eksponati-muzeyu

23. ICOM launches the Emergency Red List of Cultural Objects at Risk – Ukraine. ICOM https://icom.museum/en/news/launch-icom-red-list-ukraine/

24. Emergency Red List of Cultural Objects at Risk – Ukraine https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Emergency-Red-List-Ukraine-–-English.pdf