David vs Goliath: Moldova’s Fight Against Russian Disinformation

In November 2023, Moldova held local elections in hundreds of municipalities. The country’s ruling pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) has received over 40% of the vote and 32% of mayoral seats, but has failed to win in any of the key 11 municipalities. Russian interference in the electoral process is blamed for these PAS shortcomings. Disinformation and propaganda, among other methods, have allegedly paved the road to victory for pro-Russian candidates.

Yet another sisterly nation

Despite Moldova’s independence since 1991 and no common border with Russia, Moscow continues to consider Moldova as ‘its sphere of interest’. Reluctant to lose its clout, Russia has exploited historical ties and cultural affinities to sow discord, manipulate public opinion, and bolster pro-Russian sentiments in Moldova. Still, Russia’s vested interests in Moldova extend beyond historical and cultural ties. Economically, Russia continues to have significant leverage over Moldova, as the latter depends on electricity supplies from its breakaway region of Transnistria, backed by Russia. Additionally, Moldova's political landscape has seen figures that lean considerably towards Moscow. Notable among them are former presidents Igor Dodon and Vladimir Voronin, both of whom maintained pro-Russian stances during their tenures.

In 2020, the Moldovan electorate, dissatisfied with the previous pro-Russian governments, voted Maia Sandu to the presidency. Sandu's victory represented a break from the past, as she championed an agenda rooted in reforms, anti-corruption, and closer European integration, resulted in the EU opening accession talks with Moldova in 2023. Russia perceives this Moldova's European drift with hostility. In 2023, journalists revealed a strategy paper, allegedly developed by Russia’s secret service in 2021, that set up a 10-year plan of actions to fully bring Moldova under Russian influence. One of its methods is intensification of disinformation and propaganda campaigns in the country. This tug of war between European integration and Russian influence underscores the pivotal role that information warfare plays in the contemporary geopolitical contest for Moldova's future.

Russia's dictator Vladimir Putin, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, and a far-right Deputy PM Dmitriy Rogozin who used to fight against Moldova's troops, meeting pro-Russian Moldova's president Igor Dodon, 2017. Kremlin, CC-BY-4.0

Capitalizing on the Soviet past

Today’s Moldova consists largely of the territory known as Bessarabia. Originally part of the medieval Principality of Moldavia, Bessarabia was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812 following the Russo-Turkish War. For over a century, the region underwent administrative and cultural changes under Russian rule. Amidst the chaos of the 1917 Russian Revolution, Bessarabia’s representatives voted to unite with Romania, a decision driven by cultural and historical ties. However, the pre-World War II Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union again ‘granted’ the USSR control over Bessarabia.

To prevent further ‘reunification’ attempts, the Soviet authorities began to sever Moldova’s ties with Romania. In an artificially created Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Soviets merged parts of eastern Bessarabia with territories from the Ukrainian SSR. The Russian language was promoted. The Soviet authorities also renamed the Romanian language into Moldovan and replaced its original Latin alphabet with the Cyrillic one. Educational system additionally stressed alleged differences between the Romanian and newly created Moldovan languages. Soviet propaganda also continued to emphasize that Moldovans were a separate ethnic group from Romanians, despite the shared linguistic and cultural heritage.

In 1941, Romania aligned with Nazi Germany and recaptured Bessarabia, just to see the USSR’s Red Army regaining control over the territory in 1944. This short loss of control over Moldova has resulted in the USSR intensifying its forced russification. The Soviet authorities promoted the Russian language, suppressed Moldovan nationalism, and carried out deportations of people, which the USSR deemed as ‘enemies of the state’. The demographic landscape has also changed due to a significant influx of ethnic Russians. This process of forced russification particularly targeted the regions of Transnistria and Gagauzia sowing the seeds for future ethnic tensions.

German troops preparing to cross the Pruth river and invade Moldova in July 1941. Bundesarchive.

The Transnistria region, with its significant population of Slavic minorities and Soviet-era settlers, became the flashpoint of the identity tensions amidst the USSR dissolution and Moldovan independence. Its residents, influenced by Soviet-era policies and demographics, resisted Moldova's nationalist pull and sought closer ties with Russia, leading to the declaration of an independent Transnistrian state. This independence proclamation led to an armed conflict between Moldovan forces and Transnistrian separatists, backed by the Russian army. After almost two years of fighting, a ceasefire was brokered, but a comprehensive peace agreement remains elusive.

As of now, no UN member state has recognized Transnistria independence. The region remains under Russian administrative and military control and heavily relies on Russia’s financial injections. However, the breakaway region has one significant advantage: Moldova’s largest electricity plant, Russian-owned Cuciurgan, is located in Transnistria. Receiving Russia’s Gazprom gas supplies free-of-charge, Transnistria subsequently sells this electricity to Moldova, making up around 70% of the country’s power supply.

Alongside Transnistria's challenges, the southwestern region of Gagauzia, inhabited primarily by the Turkic-speaking Christian Gagauz people, presents a different challenge. Moldova’s drive towards potential reunification with Romania ignited fears among the Gagauz, who perceived it as a threat to their unique cultural and linguistic heritage. In 1991, the Gagauz also declared independence, yet the Moldovan central government opted for dialogue over confrontation. By 1994, negotiations resulted in the Law on the Special Legal Status of Gagauzia, granting the region autonomy within Moldova. Today, Gagauzia enjoys a considerable degree of self-rule but continues to demonstrate pro-Russian inclinations.

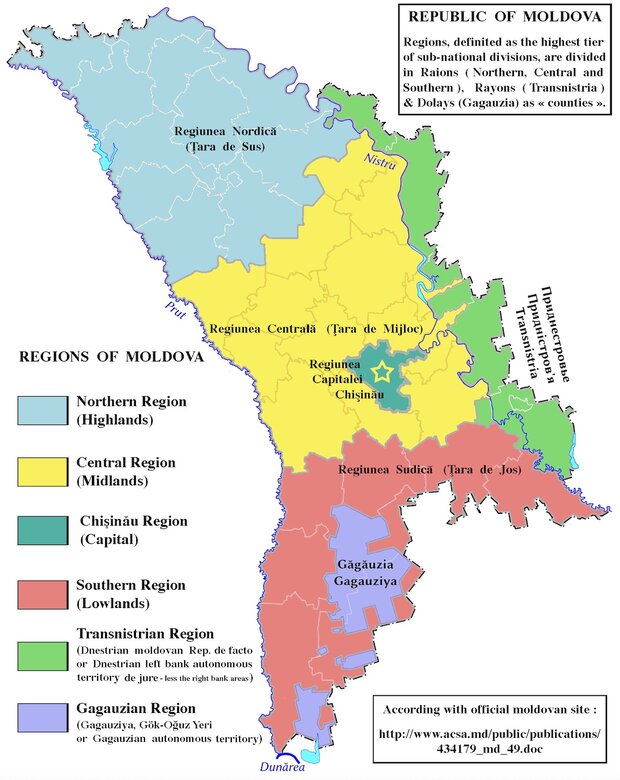

Moldova's regions. CC-BY-CA 4.0 Julieta34

Russian propaganda, Moldova edition

Russia’s disinformation and propaganda campaigns aim to advance Moscow’s geopolitical interests by undermining trust in democratic institutions and exploiting societal divisions in a targeted country. It is often hard to attribute these campaigns to Russia due to the covert nature of these activities and Russia’s ability to tactically adapt its campaigns to various contexts and targets. Similar to other countries targeted by Russian disinformation, Moldova has seen the spread of three main narratives.

Undermine the government of the country. The narrative discredits the leadership of President Maia Sandu and her pro-European stance by painting her government as weak, inefficient, and susceptible to external Western influences. Disinformation campaigns spread false stories or exaggerated claims about potential economic hardships, loss of cultural identity, and the erosion of Moldovan sovereignty under European directives. The objective is to induce scepticism about, and amplify the purported risks of, European integration.

Build up Russia. This narrative is twofold: first, it stresses the cultural, historical, and economic connections between Moldova and Russia, sentiments of Slavic brotherhood, shared Orthodox Christian faith, and the long-standing trade ties. Second, this narrative portrays Russia as a stabilizing force, a counterbalance to the allegedly aggressive Western policies. The key idea of such propaganda campaigns is to emphasize Russia's role in ensuring peace in the region, its willingness to provide economic support to Moldova, and the benefits of Moldova’s closer ties with the Russia-run Eurasian Economic Union.

Disparage Western partners. Such disinformation campaigns aim to vilify Moldova’s Western partners to discourage closer ties between them. Romania is depicted as an expansionist neighbour seeking to annex or dominate Moldova. The European Union is portrayed as a demanding partner, keen on imposing its conditions on Moldova without providing any benefits in return. There is also a consistent attempt to portray the EU as a sinking ship, embroiled in internal crises, and thus an unreliable partner for Moldova. NATO narratives are more alarmist, suggesting that any affiliation with the alliance would jeopardize Moldova's neutrality and drag the country into conflicts.

Protests in Moldova's capital Chisinau in 2009, after the parliamentary election. VargaA, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Spreading Russian propaganda

Russia propaganda in Moldova is distributed via a number of key channels. Russia-linked TV channels and radio stations, infamous for their role in spreading disinformation and propaganda, have an especially pronounced influence over older inhabitants. Until 2023, Moldova’s media landscape was dominated by channels controlled by pro-Russian oligarch Ilan Șor and the Socialist Party of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM). The PSRM, in particular, stands out as a potent media force overseeing a range of six or seven primary TV stations and an array of news portals, Telegram channels, and print outlets. To counter their influence, Moldova suspended broadcasting licences of a dozen of pro-Russian TV channels, including those owned by Ilan Șor, in the course of 2022-2023. Moldova also banned TV channel from broadcasting news and analysis programs from Russia, allowing broadcasts in Russian of only entertainment shows and movies. Additionally, the number of TV channels, obliged to produce at least 80% of content in Romanian, has been increased.

Nevertheless, Moldova’s regulatory body for media, the Audiovisual Council, cannot fully enforce the ban on Russian-linked TV channels and radio stations. TV channels and radio stations in breakaway Transnistria, which Moldova does not control, also actively spread Russian disinformation, which at times have a spillover effect in Moldova’s government-controlled territories. Russian radio stations, for instance, hijack the frequencies of Romania-language radio stations just a mere 40 kilometres away from the capital of Chișinău, broadcasting Russian propaganda content banned in Moldova. This enforcement deficiency translates into regional discrepancies across the country. Russian mass media also maintains notably strong influence in Gagauzia, where the population is still largely pro-Russian.

As Moldova blocked Russia-linked traditional media, digital platforms and social media networks, such as Facebook and Telegram, have become fertile breeding grounds for disinformation. In the past two years, Moldova's Intelligence and Security Service blocked several dozen Russian news websites for their alleged participation in an information war against Moldova. The head of one of the blocked websites, the Sputnik Moldova news agency, has also been deported from Moldova due to his alleged connections with Russian secret services. As a response, the Russian government banned entry to the head of the Audiovisual Council, Liliana Vitu, into Russia.

Russia's propaganda outlet Sputnik's press conference room. A banner reads "We say what others pass with silence". [X, formerly Twitter], euractive

However, Moldova's anti-disinformation law is proving difficult to enforce. To ban a specific online platform, the law necessitates to prove that the information, provided on this platform, is false, intended to disinform, and caused harm to an individual, an organization, or national security. This process takes significantly more time than a creation of a new online media channel. For instance, the Sputnik.md Telegram channel, known for disseminating biased or false information, amassed over 25,000 subscribers. Once this channel was banned, five mirror channels instantly appeared. Other pro-Russian channels, like Kp.md, Aif.md, and gagauznews.md, also boast substantial followings.

Russia has also turned the Orthodox Church of Moldova into a tool to exert its influence. In Moldova, the Christian-Orthodox confession is dominant, but it is a field of dispute between Russia and Romania. The Orthodox Church of Moldova, the most powerful by the number of parishes and parishioners under its authority, is part of the Russian Orthodox Church. Through the Church, Russia has been seeking to win the ‘minds and hearts’ of the parishioners, while amassing its political clout. The Church and pro-Russian politicians in Moldova have established the mutually beneficial relationship: the Church benefits from financial support, and politicians increase their visibility among citizens. Hence, Russia’s Orthodox Church uses its influence especially during electoral campaign seasons in Moldova. In 2016, church authorities urged to vote for ‘the Christian Igor Dodon’, while badmouthing Maia Sandu.

Russia’s 10-year strategy to bring Moldova under its influence assigned the Orthodox Church one of the key roles in this forced rapprochement. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia’s Orthodox Church has begun intensifying its relations with Moldova’s metropolitanate. Russia’s Patriarch Kirill presented a new decoration to the leader of the Orthodox Church of Moldova and invited him to conduct a series of religious ceremonies in the church complex within the Kremlin. These trips aim to demonstrate that Russia still has control over one of the most influential institutions in Moldova. According to opinion polls, 62.5% of Moldova's residents trust the church, more than any other institution in the country.

Moldova's democratic president Maia Sandu and Besarabia's Mitropolite Petru. Presidential Office of Moldova.

How Moldova is learning to fight back

Moldova’s government is taking steps to address disinformation in media, but the task remains challenging. In the past year, Moldova’s Audiovisual Council has enforced stringent oversight on media service providers and distributors, resulting in almost 450 sanctions for breaches of audiovisual laws. However, the council only covers TV and radio and does not exercise control over online media. Another substantial impediment is that the Audiovisual Council currently operates with a significantly understaffed team.

To improve the country’s performance in fighting off Russian disinformation, Moldova has undertaken two major steps. First, President Sandu initiated the establishment of the National Centre for Information Defence and Combating Propaganda, dubbed PATRIOT. The center will coordinate and implement the state policy on information security, will facilitate interactions between state actors and NGOs, and will identify and combat disinformation threatening national interests. The center is yet to start operating but has already drawn substantial criticism over its mandate. The Institute for European Policies and Reforms points to the need for substantial refinements of the center’s legal structure, independence, and its relationship with other relevant public bodies. Moreover, there is an apparent jurisdictional overlap between PATRIOT and other public institutions.

Second, the EU has established the European Union Civilian Mission in Moldova (EUPM Moldova) at the request of the country’s government. EUPM Moldova is tasked with strengthening Moldova's crisis management capabilities and enhancing its resilience against hybrid threats. This mandate encompasses challenges related to cybersecurity and countering foreign information manipulation and interference. The mission has a two-year tenure, spanning from April 2023 to May 2025, with a budget of €13.4 million. Besides countering disinformation, EUPM Moldova seeks to signal the EU’s commitment to support Moldova to Russia.

Conclusion

Moldova’s fight against disinformation and propaganda, generated and used by a much potent adversary, accentuates the urgency for sub-regionally coordinated disinformation response strategies. The country’s inability to protect its population from Russian disinformation during the recent electoral campaign demonstrates that such a strategy is yet to be identified. It also highlights the gargantuan effort it takes to fight Russia digitally. Its successful development, or lack of thereof, will not only be reflected during Moldova’s upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections, but also in other European countries populated by large Russian-speaking minorities.

References:

Audiovisual Council. “Noi Modificări La Codul Serviciilor Media Audiovizuale, Intrate În Vigoare.” [New Changes to the Audiovisual Media Services Code have entered into effect] Consiliul Audiovizualului Moldova, November 21, 2022. Available at: https://consiliuaudiovizual.md/news/noi-modificari-la-codul-serviciilor-media-audiovizuale-intrate-in-vigoare/?fbclid=IwAR3ebWCW4xB9PV7_cJ_eBOzTXKq690vk1s8FdBJAl1NlspoQNlWCe1y-tAA.

Canțâr, Cristian. Interview. Conducted by Adrian Mendoza. June 23, 2023.

Cibotaru, Mihaela. “Experți// Centrul „Patriot" Poate Fi Creat, Dar După Revizuirea Unor Prevederi.”[ Experts// “Patriot”center can be created, after revising some provisions] Centrum de Investigatii Jurnalistice Anticoruptie, June 18, 2023. Available at: https://anticoruptie.md/ro/stiri/experti-centrul-patriot-poate-fi-creat-dar-dupa-revizuirea-unor-prevederi.

Erlich, A., & Garner, C. (2023). Is pro-Kremlin disinformation effective? evidence from Ukraine”. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 28(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211045221

EU Partnership Mission in the Republic of Moldova (EUPM). “About EU Partnership Mission in the Republic of Moldova.” European Union External Action Service. Accessed February 13, 2024. Available at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eupm-moldova/about-eu-partnership-mission-republic-moldova_en?s=410318#68115.

Gonța, Aneta. Interview. Conducted by Adrian Mendoza. 29 June 2023

Gotișan, Victor. “Russian Soft Power in Moldova: Fake News, Media Propaganda and Information Warfare.” Zentrum Liberale Moderne, August 24, 2020. Available at: https://libmod.de/en/russian-soft-power-in-moldova-fake-news-media-propaganda-and-information-warfare/#_edn9.

Litra, Leo. “The Final Frontier: Ending Moldova’s Dependency on Russian Gas.” ECFR, November 1, 2023. https://ecfr.eu/article/the-final-frontier-ending-moldovas-dependency-on-russian-gas/.

Mendoza, Adrian (2023). “Unravelling the Web: Assessing the Impact of Russian Disinformation Campaigns on Pro-Ukrainian Residents of Germany”. Hertie School. Available at request to the author.

Sandu, Maia. “President Maia Sandu’s Message about the Initiative to Create the National Center for Information Defense and Combating Propaganda.” Presidency of the Republic of Moldova, May 29, 2023. Available at: https://presedinte.md/eng/discursuri/mesajul-presedintei-maia-sandu-despre-initiativa-de-creare-a-centrului-national-de-aparare-informationala-si-combatere-a-propagandei-patriot.

Scutaru, George, Marcu Solomon, Ecaterina Dadiverina, and Diana Baroian. “Russia’s Hybrid War in the Republic of Moldova”. New Strategy Center, April 2023.

Stăvilă, Olga. “The Audiovisual Council Presented Its Report to Parliament. Opposition Demanded Explanations for Suspension of Licence for Six TV Stations.” Radio Moldova, April 14, 2023. Available at: https://radiomoldova.md/p/10467/the-audiovisual-council-presented-its-report-to-parliament-opposition-demanded-explanations-for-suspension-of-licence-for-six-tv-stations.

Zamosteanu, Marcela, Liliana Botnariuc, Vladimir Thorik, Iurie Sanduta, Nicolae Cuschevici, and Dumitru Baciu. “Planul Kremlinului Pentru Moldova.” [The Kremlin’s plan for Moldova] Rise Moldova, March 15, 2023. Available at: https://www.rise.md/articol/planul-kremlinului-pentru-moldova/.